In this talk that I produced for Pycon USA 2021 I take a look at the Hyperloglog and Bloom Filter probabilistic data structures, using examples with the Python language and Redis with the RedisBloom module. I also subsequently gave this talk as a pre-recorded video at Pycon Australia 2021 and in a shorter form in person at Pycon Middle East / Asia, Dubai 2022 (that version’s at the bottom of this article).

You can watch the video here, the article that follows is a transcript of the talk:

I also recently did an extended version of this talk for the Developers BR Meetup group in Brazil. Scroll down to the bottom of the page to see that version.

Your support helps to fund future projects!

My slides are available as a PDF document here. If you’d like to try this out for yourself, get my code from Github.

Introduction

Hello! My name’s Simon Prickett, and this is “No, Maybe and Close Enough” where we’re going to look at some Probabilistic Data Structures with Python.

So, the problem we’re going to look at today is related to counting things. So counting things seems quite easy on the face of it, we just maintain a count of the things that we want to count and every time we see a new and different thing, we add one to that count… so how hard can this be?

Counting with Sets

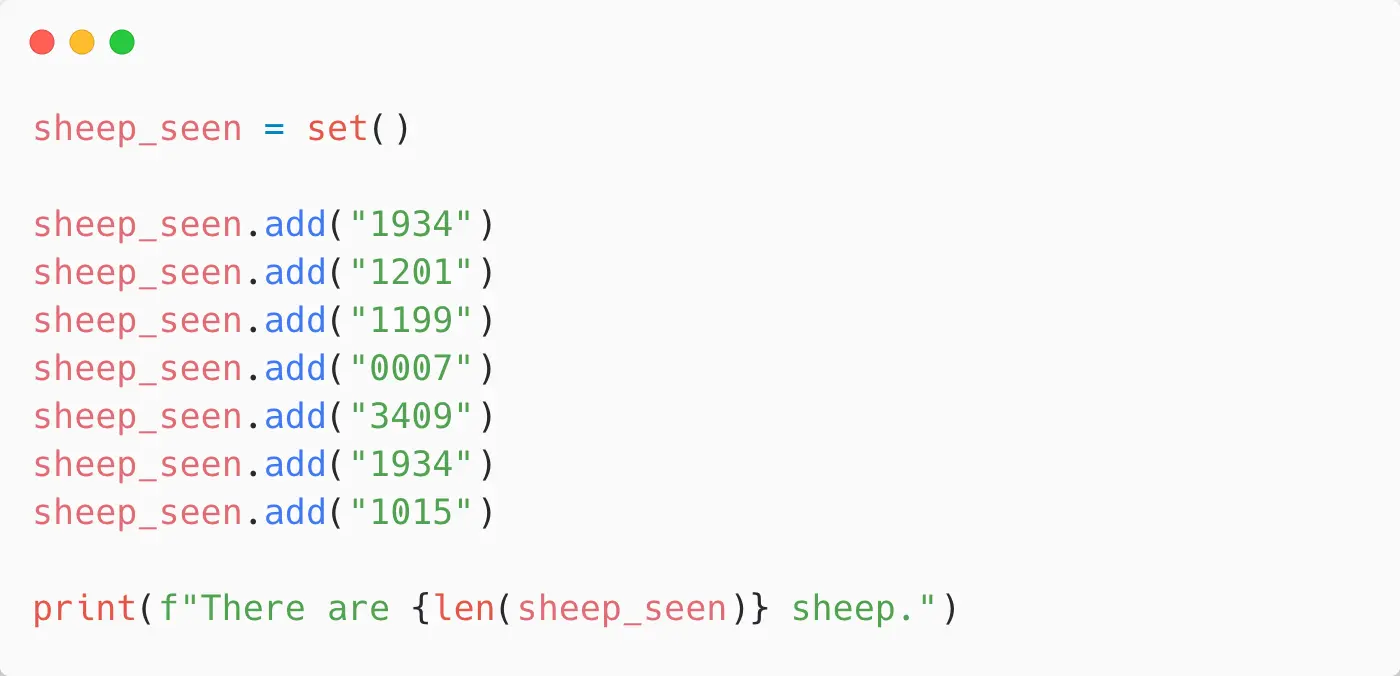

So, let’s assume we want to count sheep. So, I want to count sheep, and I’m doing that in Python. So I have here a very simple Python program that does exactly that:

Python has a set data structure built into it. These are great for this sort of problem because we can add things to a set and if we add them multiple times it will de-duplicate them, and then we can ask it how many things are in the set.

On the face of it, we can answer the question “how many sheep have I seen?” with a set.

Here, I’m declaring a set and then adding some sheep ear ID tags to it, so 1934, 1201, 1199 etc. Then further down, you’ll see I add 1934 again. That’s actually going to get de-duplicated, so when we ask this how many sheep are in the set of sheep that we’ve seen by using the len function, it’s not going to count that one twice.

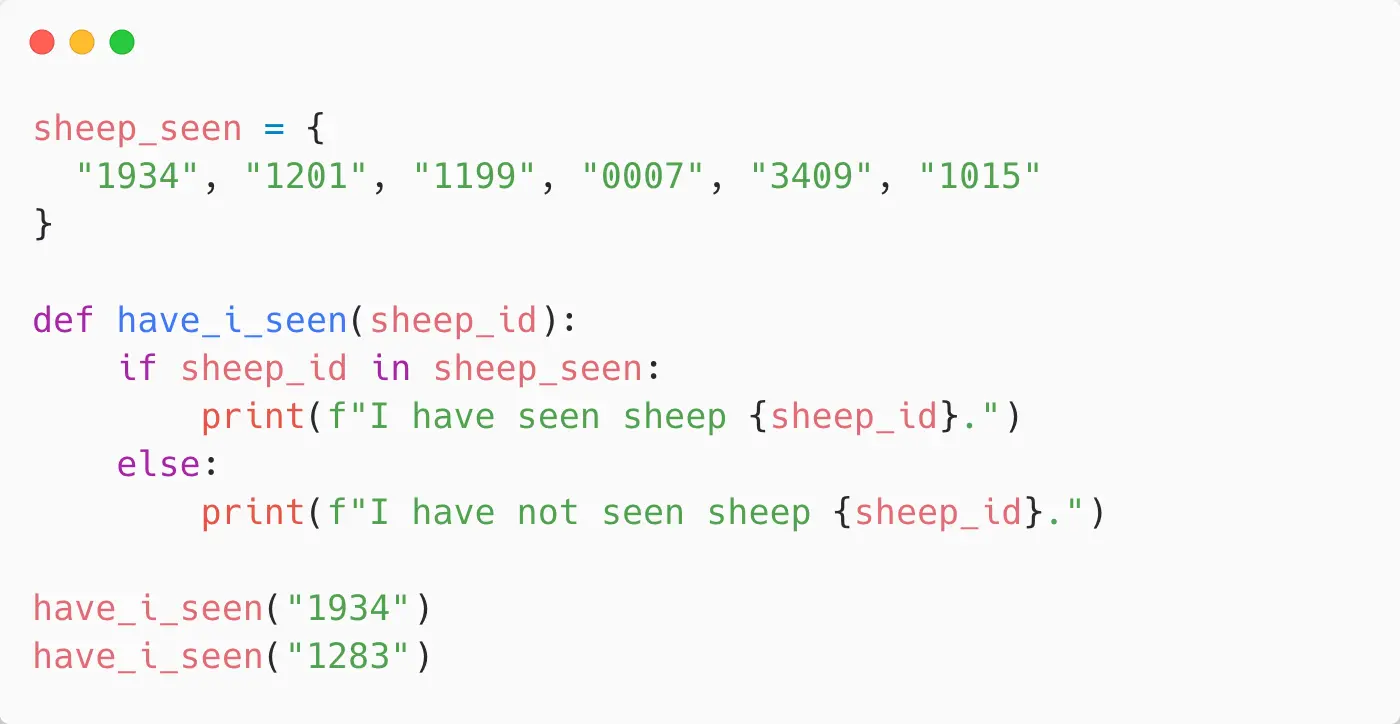

So that’s perfect! We’ve got an exact number of how many sheep we’ve seen. Another question that I might want to ask when I’m counting things is not just how many sheep have I seen, but have I seen this particular sheep? In this case, I need to be able to retrieve data from my set or data structure that I’m using to determine if we’ve seen this before, so it’s a sort of set membership query. Is sheep 1934 in the set of sheep that we’ve seen, for example. Here, again, I’m using a Python set and this seems to be a great fit for this problem:

I declare the set with some sheep tags that we’ve seen already, so 1934, 1201 etc. Then I have a simple function that just basically says “is the sheep ID passed to it in the set of sheep that we have seen?”. And it either is, or it isn’t. And that’s going to work perfectly, and it’s going to be reliable 100% of the time. So when we call have_i_seen("1934") it’s going to say “yes, we have seen sheep 1934”. When asked “have we seen 1283?” it’s going to say “no, we haven’t seen that one before” (or at least, not yet).

So when we’re counting things and we want to answer these two questions: “how many things have I seen?” (or distinct things I have seen), and “have I seen this particular distinct thing?” then a set’s got us covered: it’s done everything we need. So, that’s it, we’re done - problem solved! But… well, are we?

Issues with Being Right All the Time

The set works great, and it’s 100% accurate but we had a relatively small dataset. We had a few sheep, and we were remembering the IDs of all the sheep and the IDs were fairly short, so remembering all of those in a set and storing all of that data is not a huge problem. But, if we need to count huge numbers of distinct things - so we’re operating at internet scale, or we’re operating at Australia / New Zealand sheep farm scale then we might need to think about this again: because we might have some issues here.

At scale, when things get big with counting things, we start to hit problems with, for example, memory usage. Remembering all of the things in a set starts to get expensive in terms of the amount of memory that that set requires. It also gives us a problem with horizontal scaling. If we’re counting lots and lots and lots of things, chances are it’s not going to be one person or one process out there counting things using a local in-memory process variable to do it. We’re going to have several processes counting things, and they’re going to want to count together and maintain a common count. So, we need a way of sharing our counters and making sure that updates to them are atomic, so that we do not get false counts or we don’t have a problem if one counter goes down we’ve lost some of the data or we can’t fit all of the data in a single process’ memory.

Once we get to scale, counting things exactly starts to get very expensive in terms of memory usage, potentially time, performance and concurrency. One way that we might want to resolve that would be to move the counting problem out of memory and into a database.

Counting things with Redis

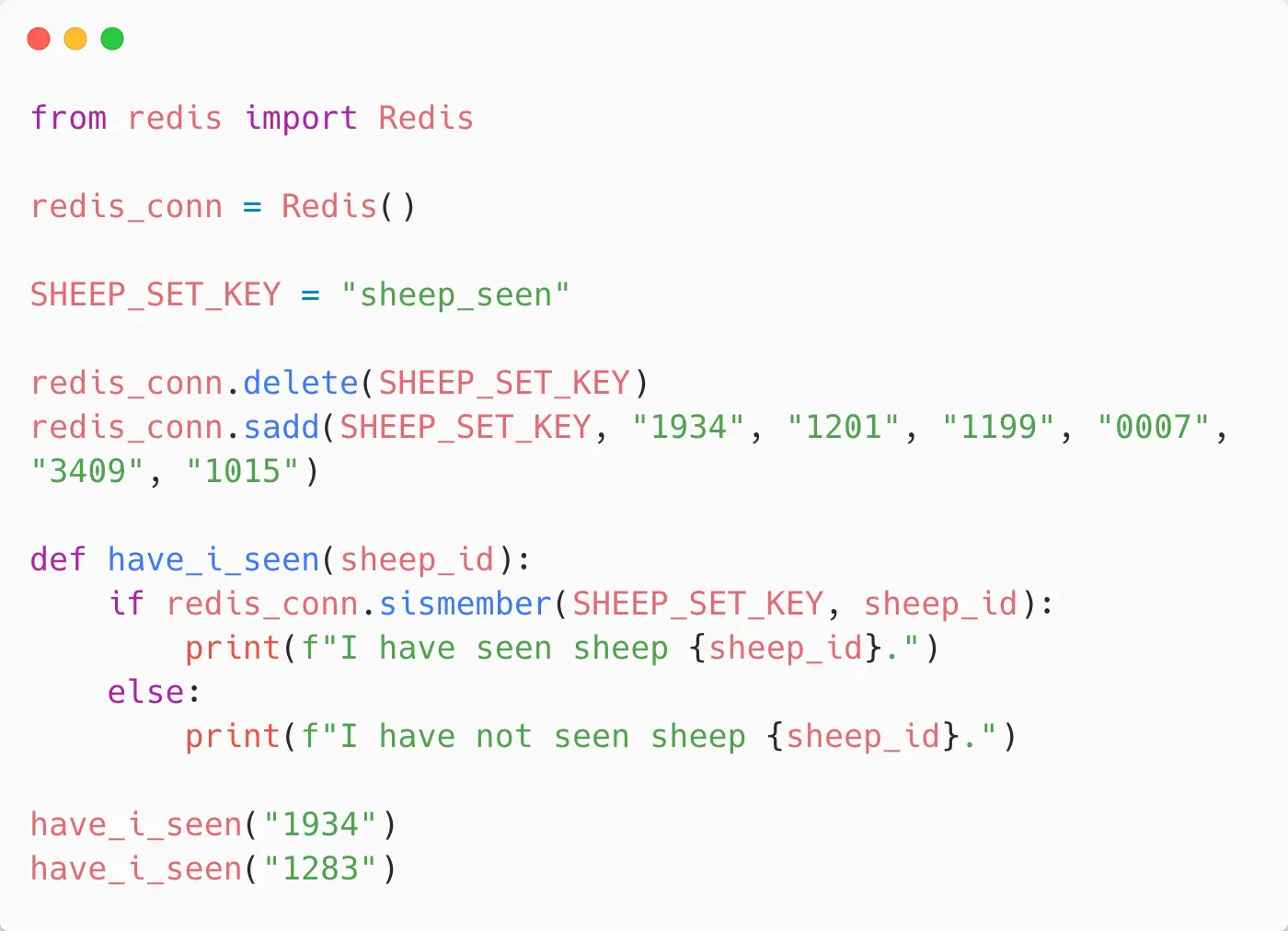

Here, I’m using the Redis database for the reason that it has a set data structure so we can take the set that we were using in Python and we can move that out of the Python code and into Redis:

This is a fairly simple code change, we just create a Redis connection using the Redis module, and we tell it what the key name of a Redis set that we want to store our sheep counts in is and we just sadd things to it. So, in Python where we were doing .add to add things to a set, for Redis it’s .sadd or “set add”. Same sort of thing, we say which set we want to put it in because we’re now using a database, so we can store multiple of these in a key/value store and we give it the sheep tags. The same behavior happens, so when I add “1934” a second time, “1934” will be de-duplicated.

And now because we’re using Redis for this and it’s out of the Python process and accessible across the network, we can connect multiple counting processes to it. So we can solve a couple of problems here: we can solve the problem of “What if I have a load of people out there counting the sheep and we want to maintain a centralized, overall count” and we’ve solved the problem of the memory limitations in a given process. The process is no longer becoming a memory hog with all of these sheep IDs in a set - we’ve moved that out into a database: in this case Redis.

But, we’ve still got the problem here of overall size. As we add more and more and more and more sheep, the dataset is still going to take up a reasonable amount of space and that’s going to grow according to how we add sheep and if we were using longer tags it would grow more every time we added a new item because we’re having to store the items.

Let’s have a look at how we can determine if we’ve seen this sheep before when using a database as well. So, here we’re again using Redis, so imagine we’d put all of our data into that set and we’ve now got shared counters and lots of people can go out and count sheep. To know if we’ve seen this sheep before we then basically have a new have_i_seen function and some pre-amble before it that clears out any old set in Redis, and sets up some sample data:

What we’re going to do now is instead of using an “if sheep tag is in the set” like we did with the Python set, we’re going to use a Redis command called SISMEMBER so “set is member” and we’re going to say “if this sheep ID is in the set then we’ve seen it, otherwise we haven’t”.

As we’d expect, that works exactly the same as it does in Python with an in-memory set but we’ve solved these two problems: we’ve solved the concurrency problem and we’ve solved the individual process memory limit problem. But, we’ve really just moved that memory problem into the database.

Tradeoffs

To solve that, and to enable counting at really large scale without chewing through a lot of memory we’re going to need to make some tradeoffs. Tradeoffs basically involve giving up one thing in exchange for another, so our sheep on the left there has its fleece, our sheep on the right has given up its fleece in exchange for being a little bit cooler but we can determine that both are sheep.

This is kind of a key thing here, we’ve been storing the whole data set and all of the data to determine which sheep we’ve seen, but can we get away with storing something about the data or bits of the data and still know that its that sheep. So, the sheep on the left and the sheep on the right, we can still tell they’re sheep even though one has lost its fleece.

Introducing Probabilistic Data Structures

This is where something called Probabilistic Data Structures come in. These are a family of data structures that make some tradeoffs. Rather than being completely accurate, they may tradeoff accuracy for some storage efficiency. We’ll see we can save a lot of memory by giving up a bit of accuracy. We might also tradeoff some functionality, so as we’ll see we can save a lot of memory by not actually storing the data. This means that we can no longer get a list back of what sheep we’ve seen but we can still determine whether we’ve seen a particular sheep with reasonable accuracy.

The other tradeoff that’s often involved with Probabilistic Data Structures is performance, but we’ll mostly be looking at accuracy, functionality and storage efficiency.

Hyperloglog

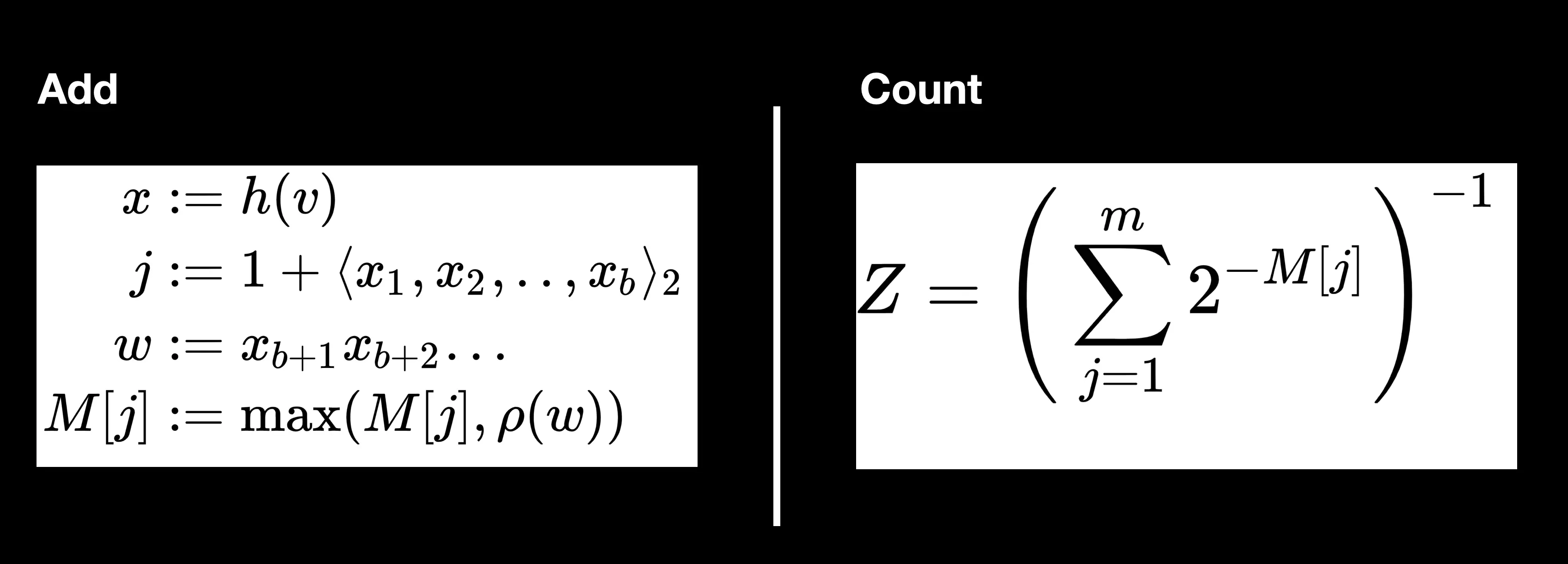

So we have two questions that we wanted to ask here: “how many sheep have I seen?” is the first one, and a data structure or an algorithm that we can use for that, which comes from the probabilistic data structures family, is called the Hyperloglog. What that does is it approximates distinct items. Basically, it guesses at the cardinality of a set based on not actually storing the data but hashing the data and storing information about it. There’s some pros and cons to this - the way the Hyperloglog works is that it’s going to run all the data through some hash functions and it’s going to look at the longest number of leading zeros in what results from that. It’s going to hash everything to a zero or one binary sequence and look for the longest sequence of leading zeros.

There’s a formula that we’ll look at but don’t need to understand which will enable us to determine if we’ve seen however many items before. It will allow us to guess the cardinality of the set with reasonable accuracy.

The benefits here are that the Hyperloglog has a similar interface to a set: we can add things to it, and we can ask it how many things are in there. It’s going to save a lot of space, because we’re using a hashing function, so it’ll come down to a fixed size data structure no matter how much data we put in there.

But, we can’t retrieve the items back again, unlike with a set. That’s both a benefit and a tradeoff, because we can’t retrieve them… that’s great in some cases where we just want a count and we don’t want the overhead of storing the information - for example if it’s personally identifiable information. It’s also a bad thing if we did want to get the information back, like we can with a set.

We can use Hyperloglog when we want to count, but we don’t necessarily need the source information back again.

The other tradeoff involved here is that it’s not built into the Python language, so we’ll need to use some sort of library implementation and we’ll need to use something else to store it in a data store, which we’ll look at.

Here are the algorithms for Hyperloglog:

This is on Wikipedia, you can read about how it works if you’re interested but basically it’s a lot of math to do with hashing things down to 0s and 1s, looking at how many leading 0s there are, keeping a count of the greatest number of leading 0s we’ve seen and then you can actually approximate the size of the dataset based on that. The take away here is that we don’t need to do that for ourselves, we’re going to use a library or another implementation that’s built into a data store and we’ll look at both of those options.

The Hyperloglog doesn’t actually answer the question “how many sheep have I seen?” for us, it’s going to answer the question “approximately how many sheep have I seen?” which may well be good enough for our dataset and it’s going to save us a lot of memory.

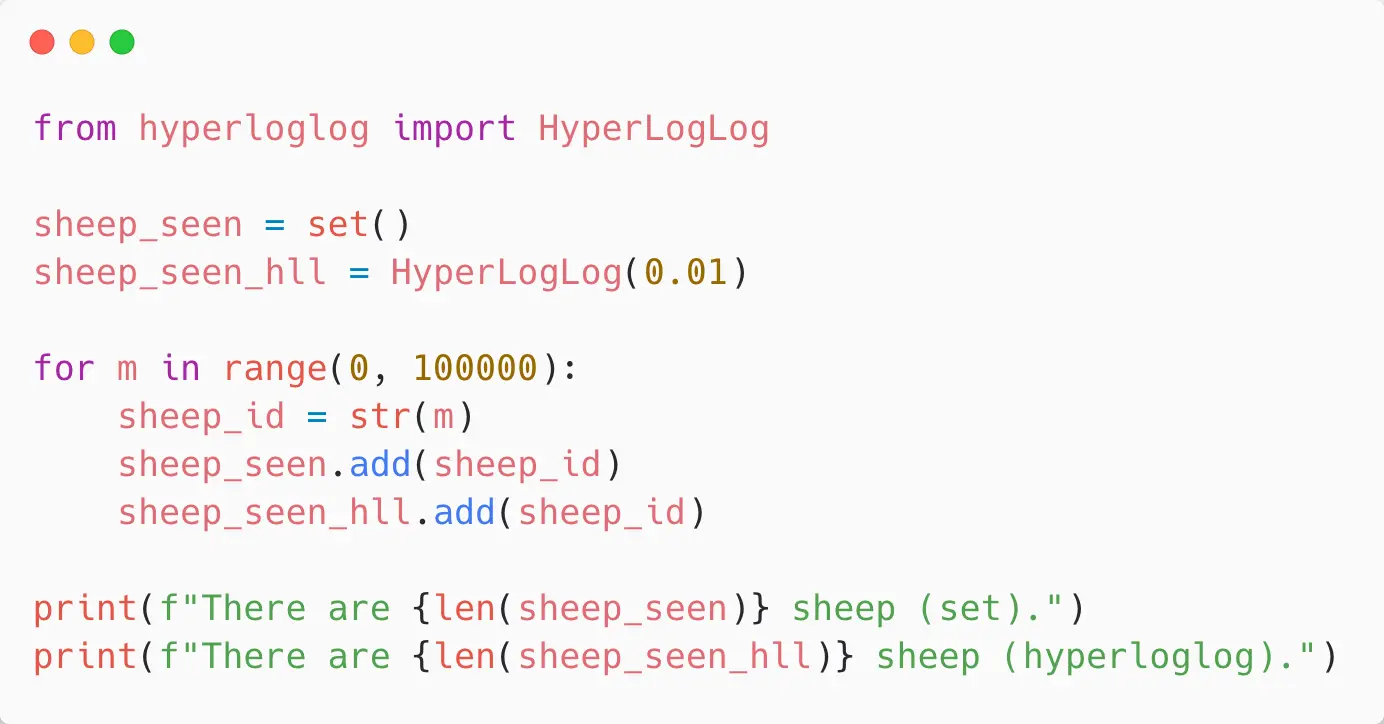

So here in a Python program, I’m using the “hyperloglog” module and I am declaring a set as well for comparison, so we’re going to see how a set compares with a Hyperloglog.

I’m declaring my Hyperloglog and I’m giving it an accuracy factor, which is something that you can tune in the algorithm so you can trade off the amount of data bits that it’s going to take for the relative accuracy of the count. And when we come to look at that with a data store, we’ll actually see how the sizes compare.

We’ve then got a loop - we’re going to add 100,000 sheep to both the Hyperloglog and the set, and then I’m going to ask both of them “how many do you have?”.

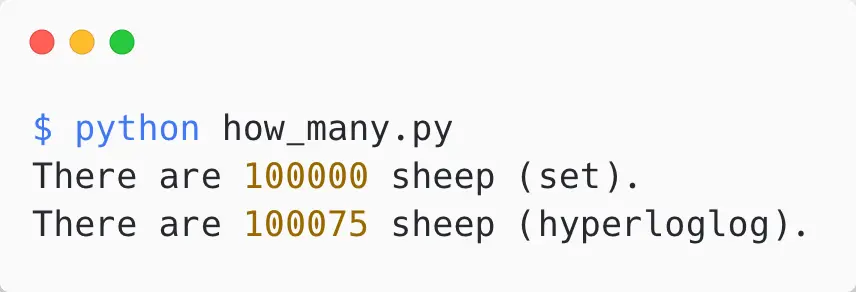

When we do that, what we’ll see is that, as we expect, the set absolutely 100% correct: we’ve got 100,000 sheep in our set and the Hyperloglog has slightly overcounted… so 100,075:

It’s within a good margin of error and the tradeoff here is that the set has taken up way more memory than the Hyperloglog has and we’ll put some numbers on that when we look at it in a database.

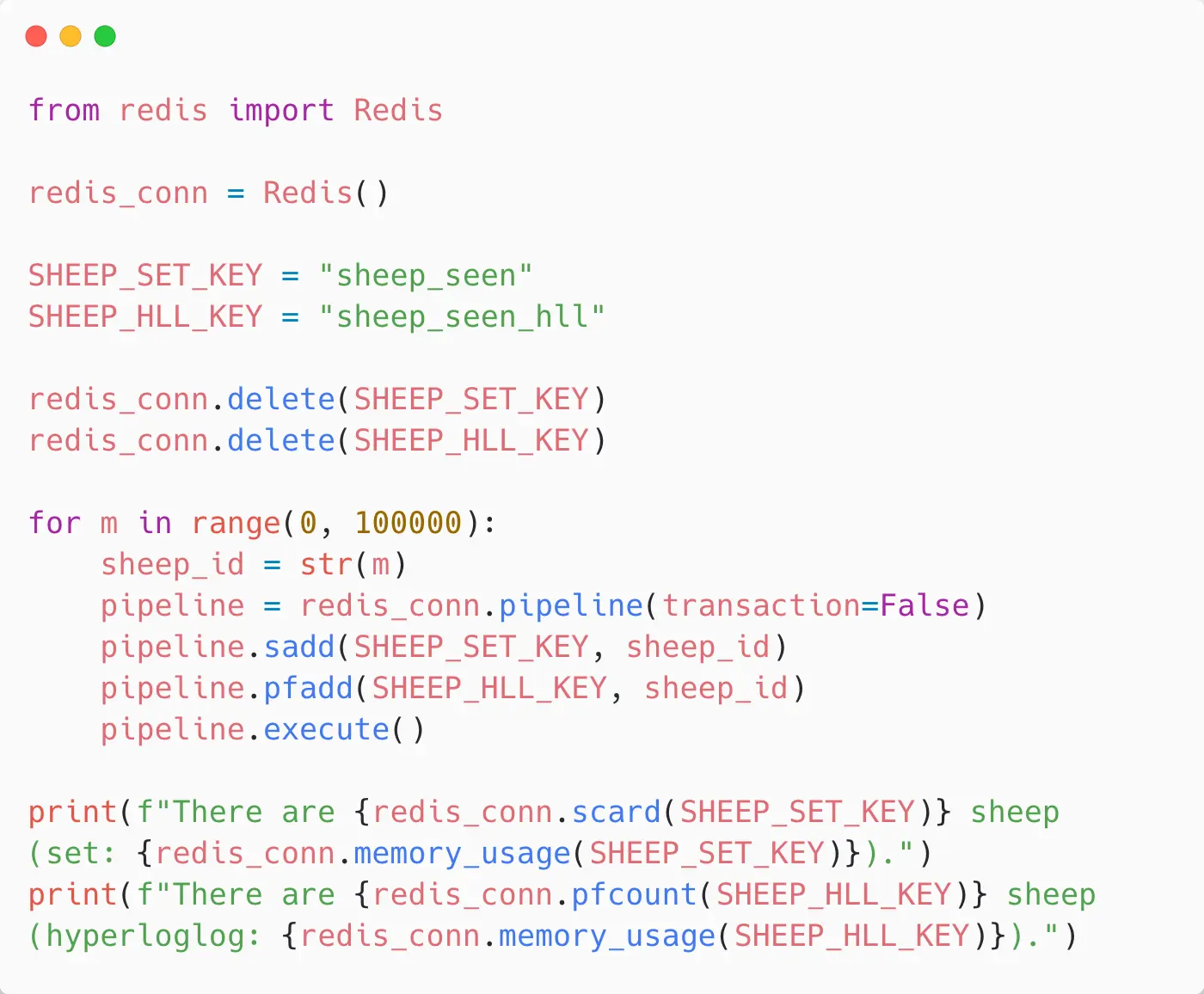

One of the reasons that I picked Redis as the data store for this is because it has sets and it also has Hyperloglog as a data type. Here I have a small Python program, it’s going to do the same thing - it’s going to store sheep in a Redis set and in a Redis Hyperloglog:

We begin by deleting those, and loop over our 100,000 sheep and add IDs to Redis for those. We put them into a set and also use the PFADD command to add them into a Hyperloglog. “PF” is Phillippe Flajolet, the French mathematician who partly came up with the Hyperloglog algorithm and the Redis commands for Hyperloglog are all named after him. And then when we’ve done that, we’ll again ask Redis “what’s the cardinality of the set?” / “how many sheep did you count?” - it’ll tell us 100,000 because it’s accurate… then it’ll tell us the approximation with the Hyperloglog so we can compare.

So here we can see that in the Redis set implementation, we got 100,000 sheep as we’d expect and it took about 4.6Mb of memory to store that. With the Hyperloglog, we got 99,565 sheep so we got pretty close to the 100,000 but it only used 12k of memory.

We could keep adding sheep to that all day and it’s only going to take 12k of memory whereas the set would have to keep growing. You can start to see some of the tradeoffs here - we’re getting an approximate count but we’re saving a lot of memory.

Bloom Filters

The second Probabilistic Data Structure I wanted to look at is the Bloom Filter. The Bloom Filter is used for our other question that we wanted to ask, which is “have I seen this sheep?”. That’s a set membership question - “is the sheep 1234 in the set of sheep that we’ve seen?”. And when we’re using a set we’ll get an absolute answer - “yes” or “no”. When we’re using a Bloom Filter, we’ll get an approximated answer, so we’ll get “absolutely no, it’s not in the set” or we’ll get “maybe it is”, meaning that there’s a high likelihood that it’s in the set.

That uncertainty comes from us not storing the data in the Bloom Filter. So, we’re going to hash the data, and we’re going to trade that memory savings off for a little bit of accuracy.

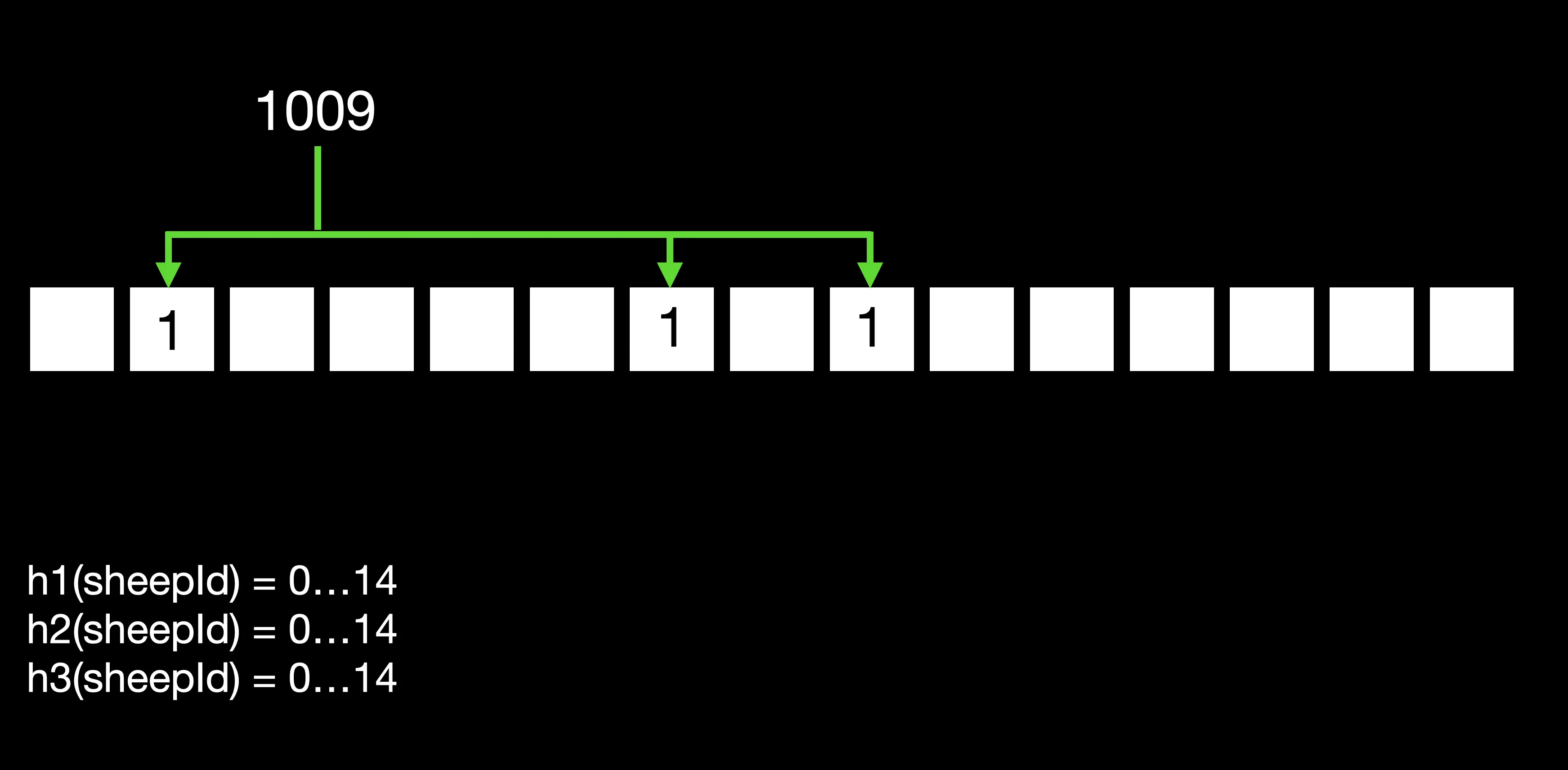

So the way the Bloom Filter works, and I have one laid out here:

is that you have a bit array, and that is however many bits you want to make it wide, so one of the things we can configure is the width of the bit array (how much memory is it going to take). Here I’ve got 15 bits as a simple example that fits on the screen. Then we configure a number of hash functions, so every time we put a new sheep ID into the filter we’re going to run it through those hash functions and they all have to return a result that varies between zero and the length of the bit array. Essentially, they’re going to identify positions in the bit array that that sheep ID hashes to, and we’re using three hash functions in our example so each sheep ID will hash to three different bits and we’ll see how that enables us to answer whether we have seen that sheep before in a “no” or “maybe” style.

If we start out with adding the ID “1009”, we have three hash functions and the first one hashes it to position 1, the second hashes it to position 6 and the third one to position 8. Then what is going to happen here is that each of those bits in the bit array is set to 1 - so we know that a hash function has resulted in that number.

Similarly, when we add more sheep, so we add sheep “9107” here, the three hash functions result in different positions and we can see in this case that “9107” generated two new positions that were previously unset in our bit array, and one existing one… so there’s potential here for, as with a lot of hashing, clashes… so the more hash functions we use and the wider the bit array, we can kind of dial some of that out. In this simple example we’re going to get some clashes.

Adding more, we add “1458” - that hashes to three things that were already taken, so we don’t set any new bits.

Now, when we want to look something up, what we do is the same thing but we look at the values in the bit array. Here when I look up sheep 2045, “have we seen sheep 2045?” the first hash function hashes to a position where we’ve got a 1, so it’s possible we have. The second one hashes to a position where we’ve got a 0 so that means we haven’t seen this sheep before. We could actually stop, and not continue with the third hashing function but for completeness I’ve shown it.

So as soon as we get one that returns a 0, we know that we haven’t seen that before - absolutely definitely. 9107 is a sheep that we have seen before - all of the hash functions land on a position that already has a 1 in it, so we can say that there is a strong likelihood that we’ve seen this sheep before.

And the reason why we can’t say that with absolute certainty is if we look at sheep 2989 here, that’s not in the set of sheep that we added at the top there, so this is not one we’ve seen before but its number hashes to positions that are all set to 1 so the Bloom Filter in this case is going to lie to us - it’s going to say “2989 - there’s a strong likelihood that sheep exists”, but actually it doesn’t.

Here, we’re trading off a lot of memory use because we’re getting down to just this bit array, and some computational time because we’re doing hashing across a number of functions but we are going to save a lot of memory and if we want to know absolutely whether we’ve seen this sheep and “no”, or “there’s a strong possibility” is an OK answer, then we can use this and we can save ourselves a lot of memory.

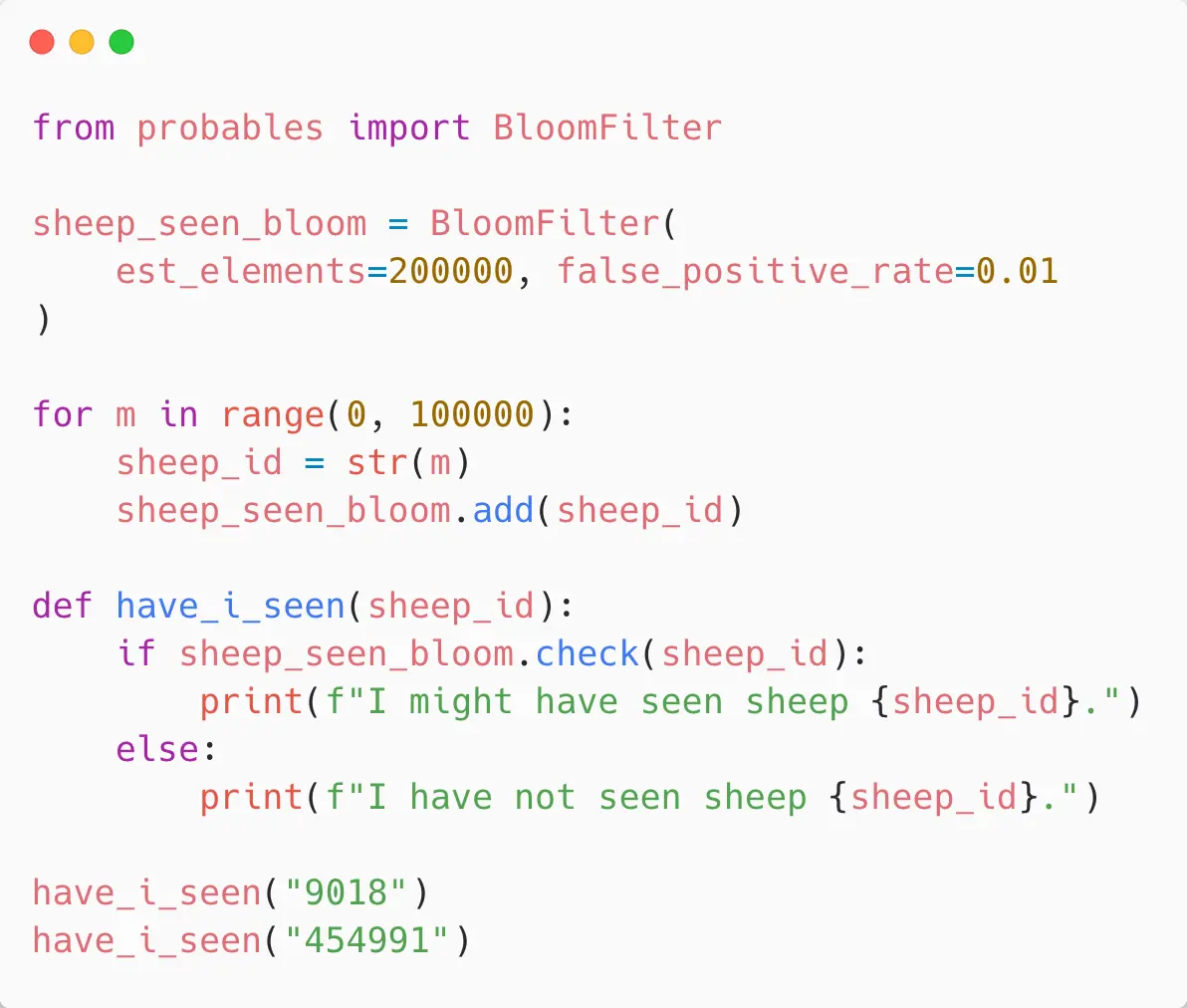

Here’s some Python code that uses this, so we’re going to use again some library code for a Bloom Filter - using “pyprobables”:

We set up a Bloom Filter and configure it. This will work out how many hashes and the bit array size etc. So we’re saying we want to store 200,000 items and we can dial in a false positive rate that’s acceptable to us. That will figure out the memory size needed, and that’s part of our tradeoffs. The more accurate we get, the more memory… the less accurate, the less memory.

Then we basically just add 100,000 sheep to the Bloom Filter in much the same way as we did with the set and our have_i_seen function is pretty much the same again… we have a check function that says “have I seen this sheep?” and it’ll say “I might have seen it” because we can’t be 100% sure or “no I definitely haven’t”.

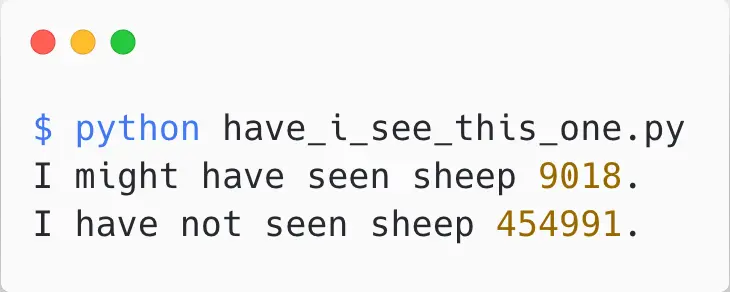

This is a good drop in for a set, the interface is very very similar, but we’re saving a lot of memory. And when we run this, you get the answers we expect, so we might have seen “9018” and it hasn’t seen “454991”.

We can also do this in data stores, so again I picked Redis as a data store for this talk because it has, via an installable module, an implementation of a Bloom Filter. Similarly I can create a Redis Bloom Filter, the BF.RESERVE command says I want to store about 200,000 items with about that accuracy.

I can add sheep into the Bloom Filter and I can ask it, “does this sheep exist in the Bloom Filter?”. And we’ll get the same sort of results as we did before:

So “I might have seen it”, or “I’ve not seen it” but we are saving a lot of memory, because now instead of using a set that’s just going to grow as we add things to it, we’ve got this fixed bit array that isn’t going to grow, but it is going to fill up as we add more sheep to it. There are strategies for stacking Bloom Filters so that as one bit array fills, another one gets put on top of it. That’s beyond the scope of this talk but it is a problem that can be solved.

When to Use Probabilistic Data Structures

When should you use Probabilistic Data Structures? Well, tradeoffs… so if an approximate count is good enough, a Hyperloglog’s great. For example, it doesn’t really matter that we know exactly how many people read that article on Medium as long as we’re in the right ballpark.

You could use a Bloom Filter when it’s OK to have some false positives. For example, “have I recommended this article on Medium to this user before?”. It doesn’t really matter if we occasionally get that wrong, and we’re saving a lot of memory - especially in those cases where we need to maintain one of these data structures per user.

It might be advantageous to use these where you don’t need to store or retrieve the original data, so if the original data is either personal stuff that you don’t want to store or it’s just never ending, so it’s a continuous stream of say temperature/humidity values.

When you’re working with huge datasets where exact strategies just aren’t going to work out for you then you’re going to have to make some tradeoffs and this family of data structures offers a good set of tradeoffs between memory and accuracy.

In Conclusion

The code that you’ve seen in this talk is in a GitHub repo, which also has a docker-compose.yml file so you can both play with it in Python just in memory, and you can play with it in Redis and have it inside a data store.

Hope you enjoyed this, and I’d love to hear what you build!

Longer Talk

I subsequently gave a longer version of this talk for the Developers BR meetup group. They very kindly put it on their YouTube channel and you can watch it here:

Shorter Version for Pycon MEA 2022

Here’s a shorter, in person, version of this talk that I gave at Pycon MEA 2022 in Dubai. This was part of the larger GitEx Global event, you can watch it on their YouTube channel:

If you’re hosting a Meetup or conference, and would like me to talk about these topics either with Python or Node.js, feel free to contact me! Hope you enjoyed this talk.

Simon Prickett

Simon Prickett

Getting Started with Express - Building an API: Part 1

Getting Started with Express - Building an API: Part 1