Server Sent Events are a standard allowing browser clients to receive a stream of updates from a server over a HTTP connection without resorting to polling. Unlike WebSockets, Server Sent Events are a one way communications channel - events flow from server to client only.

You might consider using Server Sent Events when you have some rapidly updating data to display, but you don’t want to have to poll the server. Examples might include displaying the status of a long running business process, tracking stock price updates, or showing the current number of likes on a post on a social media network.

Here’s a video of me presenting this material at San Diego JavaScript Meetup’s Fundamental JS event on 25th June 2020 - remotely due to the pandemic at the time.

Architecture

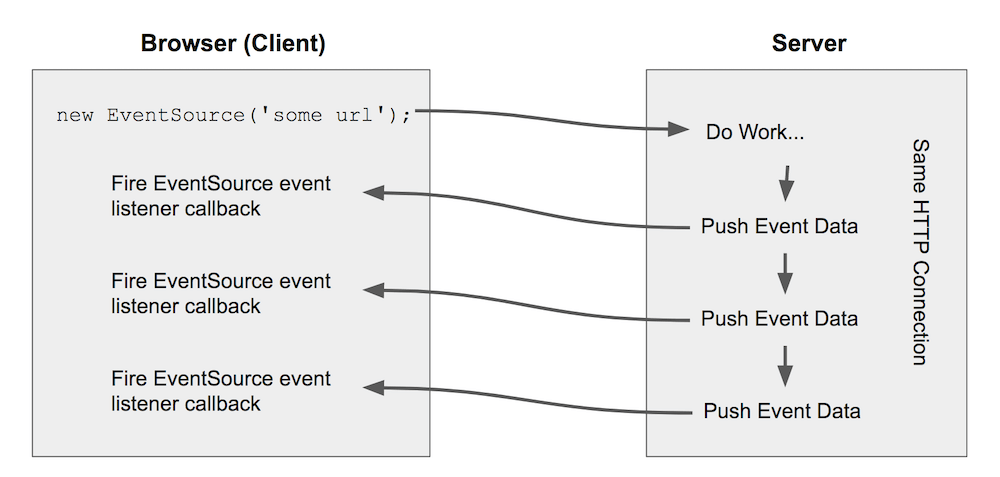

When working with Server Sent Events, communications between client and server are initiated by the client (browser). The client creates a new JavaScript EventSource object, passing it the URL of an endpoint which is expected to return a stream of events over time.

The server receives a regular HTTP request from the client (these should pass through firewalls etc like any other HTTP request which can make this method work in situations where WebSockets may be blocked). The client expects a response with a series of event messages at arbitrary times. The server needs to leave the HTTP response open until it has no more events to send, decides that the connection has been open long enough and can be considered stale, or until the client explicitly closes the initial request.

Your support helps to fund future projects!

Every time that the server writes an event to the HTTP response, the client will receive it and process it in a listener callback function. The flow of events looks roughly like this:

Message Format

The Server Sent Events standard specifies how the messages should be formatted, but does not mandate a specific payload type for them.

A stream of such events is identified using the Content-Type "text/event-stream". Each event is formatted using a set of colon separated key/value pairs with each pair terminated by a newline, and the event itself terminated by two newlines.

Here’s a template for a single event message:

id: <messageId - optional>\n

event: <eventType - optional>\n

data: <event data - plain text, JSON, ... - mandatory>\n

\n

\n

- id: A unique ID for this event (optional). The client can track these and request that the server stream events after the last one received in the event of the client becoming disconnected from the stream and reconnecting again.

- event: Specifies the type of event in the case where one event stream may have distinctly different event types. This is optional, and can be helpful for processing events on the client.

- data: The message body, there can be one or more data key/pairs in a single event message.

Here’s an example event that contains information about Qualcomm’s stock price:

id: 99\n

event: stockTicker\n

data: QCOM 64.31\n

\n

\n

In this case, the data is simple text, but it could equally be something more complex such as JSON or XML. The ID can also be any format that the server chooses to use.

Client (Browser) Implementation

The client connects to the server to receive events by declaring a new EventSource object, whose constructor takes a URL that emits a response with Content-Type "text/event-stream".

Event handler callback functions can then be registered to handle events with a specific type (event key/value pair is present). These handlers are registered using the addEventListener method of the EventSource object.

Additionally, a separate property of the EventSource object, onmessage (annoyingly not using camelCase) can be set to a callback function which will receive events that do not have the optional event key/value pair set.

The code below shows examples of both types of callback:

// Declare an EventSource

const eventSource = new EventSource('http://some.url');

// Handler for events without an event type specified

eventSource.onmessage = (e) => {

// Do something - event data etc will be in e.data

};

// Handler for events of type 'eventType' only

eventSource.addEventListener('eventType', (e) => {

// Do something - event data will be in e.data,

// message will be of type 'eventType'

});

In the callbacks, the message data can be accessed as e.data. If multiple data lines existed in the original event message, these will be concatenated together to form one string by the browser before it calls the callback. Any newline characters that separated each data line in the message will remain in the final string that the callback receives.

Important: The browser is limited to 6 open SSE connections at any one time. This is per browser, so multiple tabs open each using SSEs will count against this limit. See a discussion on Stackoverflow here for more details. Thanks to Krister Viirsaar for bringing this to my attention.

Server Side Implementation

While the client implementation has to be JavaScript as it runs in the browser, the server side can be coded in any language. As this demo was originally put together for a JavaScript Meetup group I used Node.js. The server side could just as easily have been built in Java, C, C#, PHP, Ruby, Python, Go or any language of your choosing.

The server implementation should be able to:

- Receive a HTTP request.

- Respond with one or more valid server sent event messages, using the correct message format.

- Tell the client that the

Content-Typebeing sent istext/event-streamindicating that the content will be valid server sent event messages. - Tell the client to keep the connection alive, and not cache it so that events can be sent over the same connection over time, safely reaching the client.

Code for a basic example of a server in Node.js that does this and sends an event approximately every three seconds is shown below.

const http = require('http');

http.createServer((request, response) => {

response.writeHead(200, {

Connection: 'keep-alive',

'Content-Type': 'text/event-stream',

'Cache-Control': 'no-cache'

});

let id = 1;

// Send event every 3 seconds or so forever...

setInterval(() => {

response.write(

`event: myEvent\nid: ${id}\ndata:This is event ${id}.`

);

response.write('\n\n');

id++;

}, 3000);

}).listen(5000);

Stopping an Event Stream

There’s two ways to stop an event stream, depending on whether the client or the server initiates the termination.

From the Browser / Client Side

- The browser can stop processing events by calling

.close()on theEventSourceobject. - This closes the HTTP connection — the server should detect this and stop sending further events as the client is no longer listening for them. If the server does not do this, then it will essentially be sending events out into a void.

The client side code for this is very simple:

const eventSource = new EventSource('http://url_serving_events');

...

// We want to stop receiving events now

eventSource.close();

When the server realizes that the client has closed the HTTP request, it should then close the corresponding HTTP response that it has been sending events over. This will stop the server from continuing to send events to a client that is no longer listening. Assuming the server is implemented in Node.js and that request and response are the HTTP request and response objects then the server side code looks like:

request.on('close', () => {

response.end();

console.log('Stopped sending events.');

});

From the Server Side

The server can tell the browser that it has no more events to send by taking the following actions:

- Sending a final event containing a special ID and/or data payload that the application code running in the browser recognizes as an “end of stream” event. This requires the client and server to have a shared idea of what that ID or payload looks like.

- AND by closing the HTTP connection on which events are sent to the client.

- The client should then call

.close()on theEventSourceobject to free up client side resources, ensuring no further requests are made to the server.

Assuming the server is written in Node.js, server side code to end the event stream would look like this (response is the HTTP Response object):

// Send an empty message with event ID -1

response.write('id: -1\ndata:\n\n\n');

response.end();

And the client should listen for the agreed “end of event stream” message (in this example it will have an eventId of -1):

eventSource.onmessage = (e) => {

if (e.lastEventId === '-1') {

// This is the end of the stream

app.eventSource.close();

} else {

// Process message that isn't the end of the stream...

}

};

Browser Support

Server Sent Events are supported in the major browsers (Chrome, Firefox, Safari), and now since this article was originally written also in MS Edge.

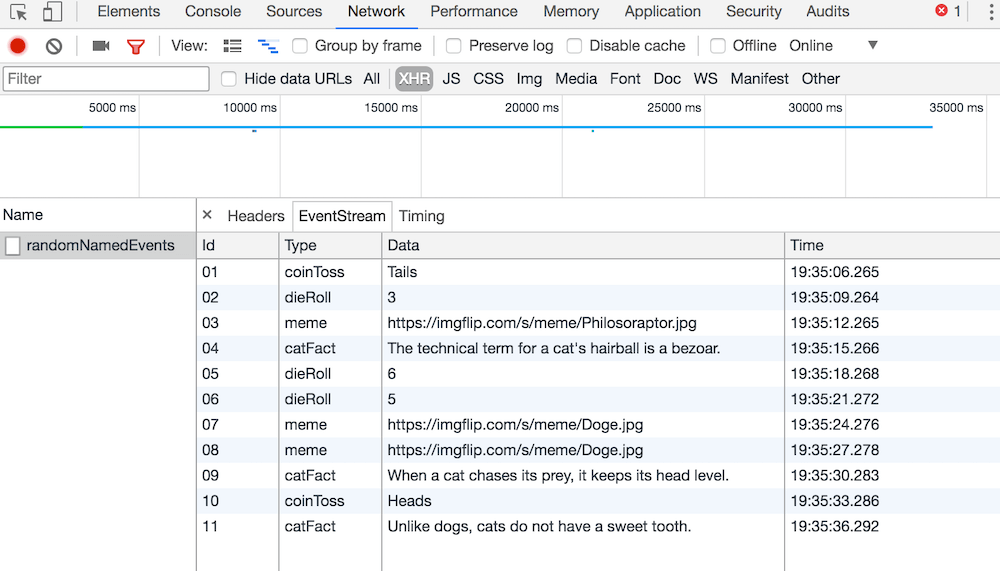

Chrome currently appears to have the best debugging support — if you select an XHR request that is receiving Server Sent Events in the Network tab, it will format the messages for you and display them in a table:

If you want to use Server Sent Events in Internet Explorer, there are polyfills available that mimic the functionality. One example is Yaffle, whose documentation also contains a list of alternative implementations.

A Quick Demo

The image below shows a simple browser application that is receiving Server Sent Events from a Node.js server. The server sends a randomly generated stream of events that can have one of four event types. Each event type contains a different type of payload:

coinToss: payload contains one of two strings — “heads” or “tails”.dieRoll: payload contains a random number from 1..6 inclusive.catFact: payload contains a cat fact as a string.meme: payload contains the URL of a meme image.

The client listens for each event type using a separate listener function for each, and updates the area of the page corresponding to that event type on receipt of an event. Additionally, event data is logged to the logging area across the bottom of the page and to the browser’s Javascript console.

The server will stop sending events after 30 have been sent, or if the user presses the “Stop Events” button before then.

If you want to grab the complete code for this project and use it yourself, it’s available on GitHub. You’ll need Node.js installed on your machine, and setup instructions are included in the project README.

Advanced — Dropped Connection & Recovery

As the HTTP connection that is used to send events to the client is open for a relatively long time, there’s a good chance that it may get dropped due to the network temporarily going away or the server deciding that it has been open long enough and terminating it. This may happen before the client has received all the events, in which case it may wish to reconnect and pick up from where it left off in the event stream.

The browser will automatically attempt to reconnect to an event source if the connection is dropped. When it does, it will send the ID of the last event that it received as HTTP header Last-Event-ID to the server in a new HTTP request. The server can then start sending events that have happened since the supplied ID, if that is possible for server-side logic to determine.

The server may also include a key/value pair in the event messages that tells the client how long to wait before retrying in the event of the server ending the connection. For example, this would specify a five second wait:

id: 99\n

event: stockTicker\n

data: QCOM 64.31\n

retry: 5000\n

\n

\n

As our demo uses randomly generated event streams, it doesn’t use this capability.

Bonus Content

This article is also available on Medium, where Billy asked:

“But how can I send SSE event to client side by other event trigger? like someone hitting my API, then i send out broadcast to the Event Source listener?”

I thought about this and replied:

Hi Billy, thanks for your feedback. I had a go at answering your question, and updated my GitHub repo with an example. To get this running, clone the GitHub repo, then:

cd src/second-demo/server

npm start

This will start the server on port 5000. This version of the server has an endpoint /subscribeToEvents that should be hit by a client wanting to get the server sent events. Try visiting:

http://localhost:5000/subscribeToEvents

From two separate browser windows. Nothing will happen until you open a third browser (or use curl from the Terminal) to visit:

http://localhost:5000/generateEvent

This simulates your API call, and will generate a random cat fact event. That event will then be sent to any clients that are registered via the subscribeToEvents endpoint.

If you hit the “stop” / “X” button on one of the browser windows that’s looking at subscribeToEvents, then refresh the window that’s pointed at generateEvent you will notice that the window you stopped doesn’t get any more events, but the other one does. Here’s a GIF that tries to demonstrate this…

How does this work? Take a look at the revised server.js code on GitHub. Whenever you visit subscribeToEvents the request and response objects for that request are added to a subscribers global object in server.js using the current timestamp as a key. I send response a keep alive response that tells it to expect server sent events, and I also add code in the request on close event to delete the subscriber key from the global subscribers object. This ensures that if the browser closes the connection, this subscriber is removed from the object storing all current subscribers.

The second endpoint generateEvent works by creating a random cat fact server sent event, then sending it to all current subscribers by looping over the keys in the subscribers object and using the response objects stored there to send the event to each browser that is registered.

Disclaimer: I knocked this out quickly late in the evening over a beer, so it may have issues I might have overlooked, but hopefully demonstrates the concept you were looking for? If you want to send events to lots of subscribers when an API event occurs, it might be worth looking at products such as Firebase?

That concludes our quick tour of Server Sent Events. Thanks for reading!

Simon Prickett

Simon Prickett

Playing with Raspberry Pi: Door Sensor Fun

Playing with Raspberry Pi: Door Sensor Fun